National Association for the Hans Jacob Honecker Families

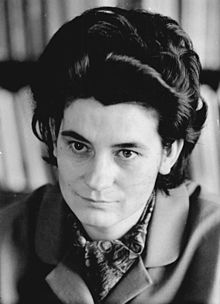

| Christa Wolf | |

|---|---|

Wolf in 1963 | |

| Born | Christa Ihlenfeld (1929-03-eighteen)18 March 1929 Landsberg an der Warthe, Germany |

| Died | 1 December 2011(2011-12-01) (anile 82) Berlin, Germany |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | German |

| Nationality | German |

| Spouse | Gerhard Wolf (b. 1928) |

Wolf in Berlin, March 2007

Christa Wolf (German: [ˈkʁɪs.ta vɔlf] ( ![]() heed ); née Ihlenfeld; xviii March 1929 – 1 Dec 2011) was a German novelist and essayist.[1] [2] She was one of the best-known writers to emerge from the former E Germany.[three] [iv]

heed ); née Ihlenfeld; xviii March 1929 – 1 Dec 2011) was a German novelist and essayist.[1] [2] She was one of the best-known writers to emerge from the former E Germany.[three] [iv]

Biography [edit]

Wolf was born the daughter of Otto and Herta Ihlenfeld, in Landsberg an der Warthe, then in the Province of Brandenburg.[iii] (The urban center is now Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poland.) After Earth War II, her family, existence Germans, were expelled from their home on what had become Polish territory. They crossed the new Oder-Neisse border in 1945 and settled in Mecklenburg, in what would become the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany.

She studied literature at the University of Jena and the University of Leipzig. After her graduation, she worked for the German Writers' Union and became an editor for a publishing visitor. While working as an editor for publishing companies Verlag Neues Leben and Mitteldeutscher Verlag and every bit a literary critic for the journal Neue deutsche Literatur, Wolf was provided contact with antifascists and Communists, many of whom had either returned from exile or from imprisonment in concentration camps. Her writings discuss political, economical, and scientific power, making her an influential spokesperson in East and West Deutschland during post-World War II for the empowerment of individuals to be active within the industrialized and patriarchal society.[v]

She joined the Socialist Unity Political party of Germany (SED) in 1949 and left information technology in June 1989, half-dozen months before the Communist regime complanate. She was a candidate fellow member of the Central Committee of the SED from 1963 to 1967. Stasi records found in 1993 showed that she worked as an informant (Inoffizieller Mitarbeiter) during the years 1959–61.[iv]

Stasi officers criticized what they chosen her "reticence", and they lost involvement in her cooperation. She was herself and so closely monitored for nearly 30 years. During the Cold State of war, Wolf was openly critical of the leadership of the German democratic republic, only she maintained a loyalty to the values of socialism and opposed German reunification.[1]

In 1961, she published Moskauer Novelle (Moscow Novella). Wolf'south breakthrough every bit a writer came in 1963 with the publication of Der geteilte Himmel (Divided Heaven, They Divided the Heaven).[2] Her subsequent works included Nachdenken über Christa T. (The Quest for Christa T., 1968), Kindheitsmuster (Patterns of Babyhood, 1976), Kein Ort. Nirgends (No Identify on Earth, 1979), Kassandra (Cassandra, 1983), Störfall (Accident, 1987), Auf dem Weg nach Tabou (On the Style to Taboo, 1994), Medea (1996), and Stadt der Engel oder The Overcoat of Dr. Freud (City of Angels or The Overcoat of Dr. Freud, 2010).

Christa T was a work that — while briefly touching on a disconnection from one's family'southward ancestral home . was primarily concerned with the experiences of a adult female feeling overwhelming societal pressure to conform.

Kassandra is perhaps Wolf's most important book, re-interpreting the battle of Troy as a state of war for economic power and a shift from a matriarchal to a patriarchal club. Was bleibt (What Remains), described her life nether Stasi surveillance, was written in 1979, but not published until 1990. Auf dem Weg nach Tabou (1995; translated as Parting from Phantoms) gathered essays, speeches, and letters written during the four years post-obit the reunification of Germany. Leibhaftig (2002) describes a woman struggling with life and death in 1980s East-German infirmary, while awaiting medicine from the Due west. Central themes in her work are German language fascism, humanity, feminism, and self-discovery. In many of her works, Wolf uses illness equally a metaphor. In a speech addressed to the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (High german Cancer Society) she says, "How we cull to speak or not to speak about illnesses such equally cancer mirrors our misgivings near society." In "Nachdenken über Christa T." (The Quest for Christa T), the protagonist dies of leukemia. This work demonstrates the dangers and consequences that happen to an private when they internalize society'south contradictions.

In Accident, the narrator'southward brother is undergoing surgery to remove a encephalon tumor a few days after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster had occurred.[six]

In 2004, she edited and published her correspondence with her United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland-based about namesake Charlotte Wolff over the years 1983–1986 (Wolf, Christa and Wolff, Charlotte (2004) Ja, unsere Kreise berühren sich: Briefe, Luchterhand Munich).

Grave of Christa Wolf, with pens left by well-wishers.

Wolf died 1 Dec 2011, anile 82, in Berlin, where she had lived with her married man, Gerhard Wolf.[7] She was buried on xiii December 2011 in Berlin's Dorotheenstadt cemetery.[8] In 2018, the city of Berlin designated her grave every bit an Ehrengrab.[nine]

Reception [edit]

Although Wolf's works were widely praised in both Germanys in the 1970s and 1980s, they have sometimes been seen as controversial since German reunification.[x] [eleven] William Dalrymple wrote that in East Federal republic of germany "writers such as Christa Wolf became irrelevant overnight once the Berlin Wall was broached".[12]

Upon publication of Was bleibt, West German critics such as Frank Schirrmacher argued that Wolf failed to criticize the absolutism of the E German Communist regime, whilst others chosen her works "moralistic". Defenders have recognized Wolf'due south office in establishing a distinctly East German literary voice.[13]

Fausto Cercignani'due south study of Wolf's before novels and essays on her later works take helped promote awareness of her narrative gifts, irrespective of her political and personal ups and downs. The emphasis placed by Cercignani on Christa Wolf's heroism has opened the fashion to subsequent studies in this direction.[fourteen]

Wolf received the Heinrich Mann Prize in 1963, the Georg Büchner Prize in 1980, and the Schiller Memorial Prize in 1983, the Geschwister-Scholl-Preis in 1987, as well as other national and international awards. Afterwards the German reunification, Wolf received further awards: in 1999 she was awarded the Elisabeth Langgässer Prize and the Nelly Sachs Literature Prize. Wolf became the offset recipient of the Deutscher Bücherpreis (German Book Prize) in 2002 for her lifetime achievement. In 2010, Wolf was awarded the Großer Literaturpreis der Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Künste.

Bibliography [edit]

Books

- Moskauer Novelle (1961)

- Der geteilte Himmel (1963). Translated as Divided Sky by Joan Becker (1965); later as They Divided the Heaven by Luise von Flotow (2013).

- Nachdenken über Christa T. (1968). The Quest for Christa T., trans. Christopher Middleton (1970).

- Till Eulenspiegel. Erzählung für den Film. (1972). With Gerhard Wolf.

- Patterns of Childhood (1980), translated from Kindheitsmuster (1976) by Ursule Molinaro and Hedwig Rappolt.

- Kein Ort. Nirgends. (1979). No Place on World, trans. Jan van Heurck (1982).

- Neue Lebensansichten eines Katers (1981)

- Kassandra (1983). Cassandra: A Novel and Four Essays, trans. Jan van Heurck (1984).

- Voraussetzungen einer Erzählung: Kassandra. (1983)

- Störfall. Nachrichten eines Tages. (1987). Accident: A Twenty-four hour period's News, trans. Heike Schwarzbauer and Rick Takvorian (1989).

- Sommerstück (1989)

- Was bleibt (1990). What Remains, trans. Martin Chalmers (1990); as well as What Remains and Other Stories, trans. Heike Schwarzbauer and Rick Takvorian (1993).

- Medea (1996). Trans. John Cullen (1998).

- Leibhaftig (2002). In the Flesh, trans. John Smith Barrett (2005).

- Stadt der Engel oder The Overcoat of Dr. Freud (2010). Metropolis of Angels or, The Overcoat of Dr. Freud, trans. Damion Searls (2013).

- August (2012). Trans. Katy Derbyshire (2014).

- Nachruf auf Lebende. Die Flucht. (2014)

Anthologies

- Lesen und Schreiben. Aufsätze und Betrachtungen (1972). The Reader and the Writer, trans. Joan Becker (1977).

- The Fourth Dimension: Interviews with Christa Wolf (1988). Trans. Hilary Pilkington

- The Writer's Dimension: Selected Essays (1993). Trans. Jan van Heurck.

- Auf dem Weg nach Tabou. Texte 1990–1994 (1994). Parting from Phantoms, trans. January van Heurck (1997).

- Ein Tag im Jahr. 1960–2000 (2003). One Twenty-four hours a Year, trans. Lowell A. Bangerter (2007)

References [edit]

- ^ a b A writer who spanned Deutschland's Due east-West separate dies in Berlin (obituary), Barbara Garde, Deutsche Welle, one December 2011

- ^ a b Acclaimed Author Christa Wolf Dies at 82 (obituary), Der Spiegel, 1 December 2011.

- ^ a b Christa Wolf obituary, Kate Webb, The Guardian, 1 Dec 2011

- ^ a b Christa Wolf obituary, The Telegraph, ii December 2011.

- ^ Frederiksen, Elke P.; Ametsbichler, Elizabeth G. (1998). Women Writers in German-Speaking Countries: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Press. pp. 485, 486.

- ^ Costabile-Heming, Carol Anne (i September 2010). "Illness as Metaphor: Christa Wolf, the Gdr, and Across". Symposium. 64 (iii): 203. doi:x.1080/00397709.2010.502485. S2CID 142994254.

- ^ "Schriftstellerin Christa Wolf ist tot". Der Tagesspiegel. 1 Dec 2011.

- ^ Braun, Volker (15 Dec 2011). "Ein Schutzengelgeschwader". Dice Zeit . Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Ehrengräber für Klaus Schütz und Christa Wolf". Süddeutsche Zeitung. dpa. 14 August 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Myra N. Honey. Christa Wolf and the Conscience of History. Peter Lang, 1991. p. i.

- ^ Gail Finney. Christa Wolf. Twayne, 1999. p. 9

- ^ Dalrymple, William. "Novel explosives of the Common cold War". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Alt URL

- ^ Augustine, Dolores L. (2004). "The Impact of Two Reunification-Era Debates on the East German Sense of Identity". High german Studies Review. High german Studies Association. 27 (three): 569–571. doi:10.2307/4140983. JSTOR 4140983. .

- ^ Fausto Cercignani, Existenz und Heldentum bei Christa Wolf. "Der geteilte Himmel" und "Kassandra" (Beingness and Heroism in Christa Wolf. "Divided Heaven" and "Cassandra"), Würzburg, Königshausen & Neumann, 1988. For subsequent essays come across http://en.scientificcommons.org/fausto_cercignani.

External links [edit]

- Christa Wolf: Biography at FemBio – Notable Women International

- The quest for Christa Wolf an interview with Hanns-Bruno Kammertöns and Stephan Lebert about private chats with Honecker, a German lodge in cheque mate, the influence of Goethe, the shortcomings of Brecht, and the lasting effects of Utopia at signandsight.com.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christa_Wolf

0 Response to "National Association for the Hans Jacob Honecker Families"

Post a Comment